More than two dozen Indigenous water and wastewater employees are working toward their diploma at Thompson Rivers University (TRU) in a program customized to serve their needs as well as the needs of their 23 communities throughout B.C.

The students are participating in a Water and Wastewater Technology diploma funded by the federal government. They will complete the two-year program over the next four years to allow for a work-life balance as they continue working in their communities alongside their studies.

The program covers the operation, maintenance and treatment of water and wastewater systems using both in-class time and hands-on learning.

“It’s a very multi-disciplinary field,” says Satwinder Paul, associate teaching professor and program co-ordinator. The program focuses on protecting public health and the environment. “They’re learning about water chemistry, water sciences, mathematics. But they’re also learning about mechanical, electrical and instrumentation components.”

When students graduate, they have the education and skills to work in basic to advanced water and wastewater treatment systems.

The program aligns with TRU’s strategic goals as well, said School of Trades and Technology Dean Baldev Pooni.

“Two of the goals are ‘Eliminate achievement gap’ and ‘Honouring truth and reconciliation rights,’” he said. “This program contributes to these goals in a small but effective way for the Indigenous communities.”

This is the fourth time the program has been offered in partnership with the federal government, and the first group of new students since the pandemic. Since receiving a request from the federal government to offer the program again, it took two years to reach out to 197 Indigenous communities throughout B.C., recruit and create this class.

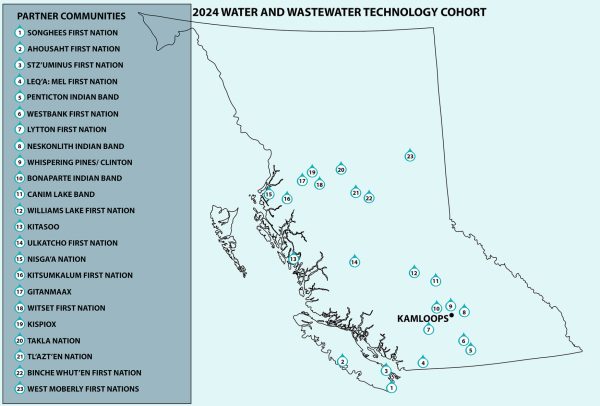

Map of water and wastewater technology cohort 2024

Paul relied on existing relationships with those communities to put the word out.

“We recruit them, we help them fill out their applications and related documents, and collect their transcripts,” she says of the prospective students. “All the information was disseminated and collected here and then it was passed on to the registrar to do their part.”

Entry qualifications require prospective students to have their Grade 12 diploma (or equivalent) and to be working with their nation’s water or wastewater treatment department.

Full support from their communities is required as the delivery format is intensive. Their course work is divided into four terms. The first term, which runs from October 2024 to March 2025, sees students attend classes for a full seven-day week each month for seven-hour days.

The latest cohort includes students from 23 Indigenous communities from as close as Whispering Pines and as far as West Moberly Nation. They’re set to graduate in 2028.

The program responds directly to community requests for education, says Tina Matthew, executive director of TRU’s Office of Indigenous Education.

“This program meets the national and provincial need for safe, drinkable water in rural and remote Indigenous communities,” she says. “When so many First Nations communities in this province do not have access to clean, safe drinking water, this provides an opportunity for TRU to provide invaluable training for First Nations individuals to become certified technicians who live and work in their own communities.”

For Krista Derrickson, manager of utilities and public works for the Westbank First Nation, the program is an opportunity to add even more education to her tool kit.

Derrickson has worked in the industry for more than 20 years and is certified as both a water and a wastewater operator, but is looking forward to adding a water quality certification.

“I just thought it was a great opportunity to get education in a format that I feel will be more supportive,” she said.

While the federal government has made headway in addressing long-term water quality issues at Indigenous communities across the country (there are currently no long-term boil water advisories in B.C.) there is still progress to be made.

That’s where these grads come in. They’ll be ensuring the water and wastewater in their communities are properly treated for future generations.