She’s the world’s first Canada Research Chair in Indigenizing higher education. And she has provided face masks to communities across Canada, to the Navajo Nation in the USA and even to Israel.

Dr. Shelly Johnson is working full-time from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. But her skills with the sewing machine and her network of contacts from Indigenous communities and research has resulted in her making almost 700 masks for people who need them. Especially in Indigenous communities.

It started with a simple request from her daughter Kristen Cotter, who is a registered nurse on Vancouver Island. About two and a half months ago, she became quite sick and although she tested negative for COVID-19, she had concerns as the pandemic was ramping up and personal protective equipment supplies were low.

“It was very tense in the beginning, because they didn’t know what was coming down and everybody was getting ready for a worst-case scenario,” said Johnson, an associate professor in the Faculty of Education and Social Work.

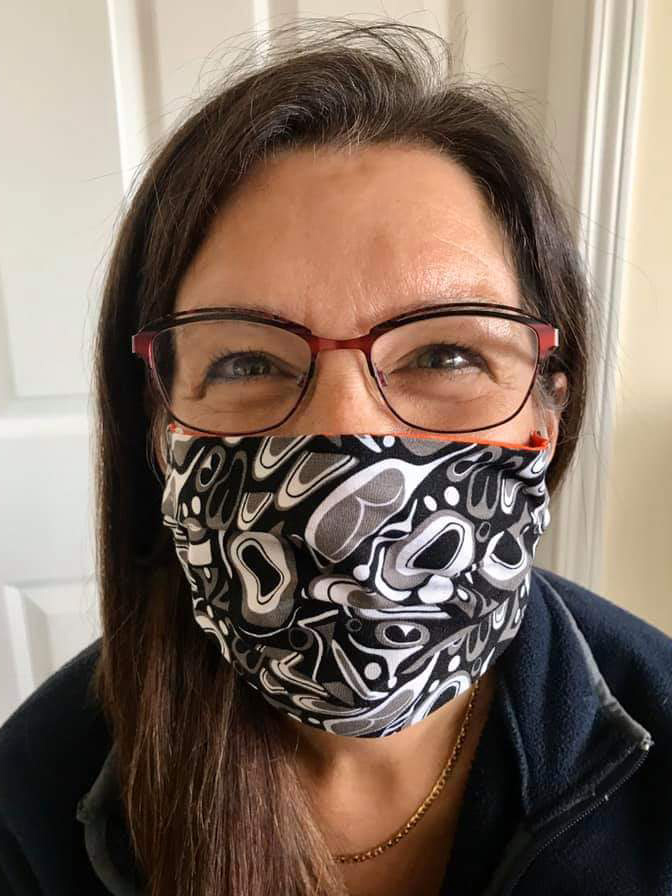

Johnson sews traditional star blankets, and she had a large stock of Indigenous-patterned fabric at home. So she made a face mask for her daughter, as well as for herself and her husband, Myles Clay.

Johnson felt the need to keep her family safe, especially in light of the fact it was torn apart by the 1919 pandemic.

Her grandmother was orphaned. She not only lost both of her parents within a day, but her siblings were split apart, divided up among five different foster homes across three Canadian provinces. Those events changed the family right at its core.

Of course you help

So when Johnson posted a few photos of her masks on Facebook and started getting requests from Indigenous communities desperately needing them, of course, she said yes.

Victor Tom, band manager with the Stellat’en First Nation in Fraser Lake, put in a request because there was a great need for masks in his community.

“He called me and asked if I could make 100 for their First Nation. I think I had made three (at that time),” said Johnson, laughing at the recollection.

“When Indigenous people ask ‘Can you help,’ our teachings are, of course you help.”

Tom knew the band manager at Cheslatta First Nation in Burns Lake, who requested 50 masks. Johnson and her husband went into manufacturing mode every weekend.

“An important part of our Saulteaux teachings is that my purpose in life is to help other people. That’s why we’re here.”

Then the BC Nurses Union council asked for masks for 25 members required to use masks when they travel. They took photos of themselves in their masks and posted them on social media.

The Ending Violence Association of BC, which operates women’s transition homes in Vancouver and serves many Indigenous women, got in touch. Vancouver’s Mobile Access program, which deals with severely marginalized people in the Downtown Eastside, requested 15 masks.

The request list kept growing: a healing centre in the Northwest Territories, a BC healing lodge for incarcerated people, Elders living in intergenerational housing, a health agency in Kamloops, First Nations throughout BC, two former students living in Israel, the Navajo Nation in the US hit hard by COVID-19.

Given from the heart

Johnson, who is from the Keeseekoose First Nation in Saskatchewan, realized it was getting too big. She turned to a Facebook group, Sew the Curve Kamloops, for some assistance.

“You support other people through this. And obviously, because I’m Indigenous, I want to provide as much support as I can to Indigenous communities,” she said.

“It’s been interesting to me how many family members have reached out to me on behalf of Elders. And they’ll send me a photo of their grandpa wearing a mask. . . . I didn’t realize how ill-prepared the hospitals and long-term-care facilities and some of our communities are. And it just fits with the values and principles I grew up with, your purpose in life is to help others.”

Every mask was given freely, as a gift. But some have given back, despite Johnson’s insistence that this was purely from the heart.

“I always told my kids when they were young, in a crisis you have to look for the helpers. And that’s your responsibility too,” she said.

“For me, it’s really highlighted how research and relationship building and community is so important for Indigenous people. Seeing a need and responding when people say, can you help?”

NOTE: Since this story was published, Johnson has been approached by the Assembly of First Nations in Ottawa to be included on a national list of Indigenous people providing personal protective equipment during the pandemic.