When second-year TRU Law student Charlotte Munroe stood in front of a class recently, she was not making a regular presentation. Munroe, along with her sister Seraphine and father Jim, were special guests in Associate Professor Katie Sykes‘ Property Law class.

The trio was there to talk about traditional law and governance structures, sharing the journey their family and community have taken over the past 20 years to protect a 17,000-hectare parcel of land called Maiyoo Keyoh, about 40 km east of Fort St. James in northern BC.

The presentation, Sykes says, helped her and her students understand the law of Aboriginal title and land claims beyond abstract legal principles.

“They brought these concepts to life in a much more vivid and moving way, through the story of their connection to the land and their long struggle to protect it,” she said.

After two decades of collecting documents, conducting land-use and occupancy studies, ethnohistorical reports, consulting with lawyers and submitting quasi-judicial reviews, the Maiyoo Keyoh Society is preparing to file a title claim in 2018 that echos the magnitude of the historic BC title claims of Delgamuukw (1997), Haida Nation (2004) and Tsilhqot’in (2014).

Jim Munroe, president of the Maiyoo Keyoh Society, says the information they compiled with help from UBC forestry students, lawyers, ethnographers and others, amounts to prima facie evidence for their case.

In the course of the research, the family also discovered that an ancestral headdress was on display at a museum in Ontario. Read: Family history inspires next generation

“I have been told by experts that our land-use study is the largest, most comprehensive and most defensible study out there. Of all the First Nations in BC, apparently we are in the top ten percent for readiness,” Jim Munroe stated, adding how thankful he is for all of the support and free help the group has received.

Munroe estimates the value of the work done for the Maiyoo Keyoh at between $2-3 million dollars. That, he said, indicates another flaw in the system.

“The burden of proof is on Aboriginal groups to provide evidence for a claim, but what kind of band or keyoh has that kind of staying power and resources? We had to ask for donations from our ethnographer and our lawyer.”

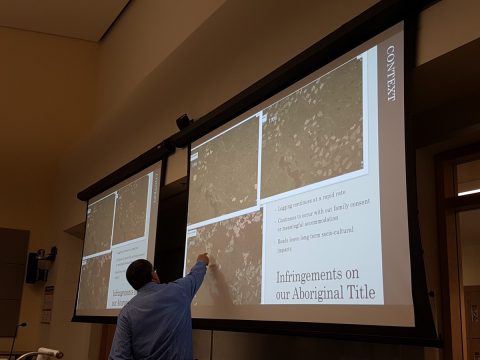

Jim Munroe points out the increasing number of logging cutblocks over time within the Maiyoo Keyoh.

A keyoh is a traditional territory belonging to a family group. The Maiyoo Keyoh is one of 42 keyohs around Fort. St. James, and was present before Europeans arrived and is traced from the early 19th century. Keyohs are also economic and political units that the Stuart Lake Carrier society uses even today.

The Munroes said modern logging practices are encroaching on their resources and disrupting their ability to be self-sustaining.

“We want to have a voice in how to protect some of our interests so that we can continue to hunt, trap and fish in our traditional territory,” said Jim Munroe.

The challenge they face, he continued, is that keyohs are not legally recognized by the government; their boundaries exist only within statutory Indian Act band asserted territories — a colonial provision the family says fosters a parallel system that leaves the customary keyoh inhabitants at the mercy of government-band relations.

“It’s contentious,” said Seraphine Munroe, a UBC masters of forestry student, referring to the political pressure it puts on the keyohs and the dynamics within their band. “It’s disruptive socioeconomically, and also in regard to the keyoh boundaries,” she added.

“The keyoh is the affected stakeholder but the Indian Act band is the interested stakeholder. So the government says to the keyohs, talk to your band. But capacities can be lacking,” she continued, noting that the dual interests/systems of the Indian Act band and the keyohs is counter to building an integrated governance system.

Beyond the legal framework, this issue also weaves itself into a significant national dialogue on 21st century relationships between and among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

“The Supreme Court of Canada has said that the constitutional protection of Aboriginal rights and title to land is fundamentally about reconciliation,” explained Sykes.

“For our students to learn this area of law through a lens of reconciliation, it’s so important to see it from the point of view of Indigenous people and to hear their voices, and I’m very grateful that we had that opportunity,” she said.

The Munroe family’s story also reflects the university’s response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission‘s calls to action, in particular to indigenize the curriculum within a pan-institutional initiative called Coyote Brings Food.

This project aims to transform the experience and understanding of students, faculty, staff and community partners about the critical importance of Indigenous history, values and traditions to the past, present and future of Canada.

Meanwhile, Charlotte Munroe shared some closing thoughts, professional and personal, with her student colleagues. “This is a unique experience for you. As law students, you read about this stuff, but you don’t typically get the inside scoop.

“For me, I have two children, so this is also about the legacy I want to leave for them.”