Chris Hadfield is back on Earth after five months commanding the International Space Station. The retired astronaut shared his insights from life in space with students of all ages at TRU’s Alumni Theatre on October 4, prior to delivering the President’s Lecture to an audience of over 1,300 people. Here we provide more of Hadfield’s question period which was excerpted in the Fall 2013 issue of Bridges Magazine.

I’ve flown in space three times on three different space ships. The first time was almost 20 years ago. I launched on a space shuttle and went to Russian Space Station, which was called Mir. … I helped build part of that on my first flight, using CanadArm.

On my second flight, I helped build the International Space Station…. During that flight I had the chance to build Canadarm II, to go outside on space walks. And I was lucky enough to be Canada’s first space walker. … Space walking is a phenomenal experience, to be outside in a one-person space ship—which is what a space suit is—holding on with one hand, in between the whole world and the universe, and you’re by yourself, trying to soak that up. It’s an amazing place to be. …

Then on my third flight, we launched on a Russian space ship, on a Soyuz. … First you have to learn how to fly the Soyuz, but none of the people who teach you how to fly the Soyuz speak English, so of course first you have to learn to speak Russian. … Then you get to fly a new rocket ship, which is a lot of fun. And then go live on the space station and take care of that ship and those people and run all those experiments for half a year. A phenomenal bunch of things to happen to this little Canadian kid.

Q: What made you want to be an astronaut?

When I was just about to turn 10, on the news were the very first three astronauts to go to the moon. Mike, Neil, and Buzz. … Pretty amazing. When Neil came to the spot to land his lunar lander, they didn’t have good pictures, the spot was covered in boulders… So Neil said we’ve got to go somewhere else. … When he finally landed, he had 16 seconds of fuel left when he finally landed his little space ship. I thought Neil was the coolest guy in the world, for having been able to do that, and Buzz also. I knew I was going to grow up to be something, why don’t I grow up to be that? That’s a cool thing. I could be anything, why not be that?

At the time, it wasn’t just hard, it was impossible. There was no Canadian astronaut program…. But I figured I’m nine, what do I know, and I figured until this morning, it was impossible to walk on the moon. Things change. So I’m just going to start getting myself ready, and see what happens. I actually consciously decided when I was nine years old, to be an astronaut when I grow up. And amazingly enough, it worked. So my career was chosen by a nine-year-old kid. Let me take it slightly further.

You are the product of your decision-making, to a very large degree, and what you decide to do today helps shape what you’re going to wake up as tomorrow. If you decided, today I’m going to eat 15 pounds of ice cream, you would have to deal with the consequences of that tomorrow—or maybe slightly sooner. Or if you said, today I’m going to do a hundred push ups. Or if you said, this week I’m going to read an entire book about, whatever. … This week I’m going to learn that. At the end of the week, you would have slightly changed who you are, even if you don’t mean to.

So I just decided I was going to slightly change myself into an astronaut. And maybe someday Canada would say, “Hey, we’re looking for someone who we think would be a good astronaut, let’s pick from whoever’s ready.” And that’s how it worked for me.

Just think about it when you’re making all those tiny decisions in a day… those are the ones that actually determine who you are. And if you keep some sort of distant goal in mind, it probably won’t turn out the way you want, exactly, but if you make all the little decisions it may at least go in a direction that you like. It may even turn out that you make it all the way and get to fly a space ship.

Retired Commander Chris Hadfield tours TRU’s Observatory on October 4 as part of his visit to deliver the President’s Lecture.

Q: What are your thoughts on civilian space travel?

Real private space flight is just beginning, it hasn’t really started yet, and that is with companies that are trying to take private paying passengers to go to space. … They want to fly around weightless, and they want to look out the window and see the universe, and see the world. I think that’s what people want to buy.

Richard Branson, who’s a brilliant guy, is dyslexic, so he learns things quite differently, but it’s given him a different way of thinking of things—it’s turned him into really successful businessman, one of the most successful in the world. … He started this company… his brand is called Virgin… and he called it Virgin Galactic. He tried to find a space ship that could take people to space that they could afford.

There’s a company out in California that built this little tiny rocket ship… It’ll go straight up, so you’re squished down in your seat for a while, and then the engines shut off. And then it’s going to just get up to space. But the real question for that is where does space start? Because the atmosphere isn’t like a cliff… it just gets thinner and thinner. We decided a long time ago that space starts 100 kilometres up. It’s just arbitrary.

So his space ship, in order to qualify, has to get over 100 kilometres. So they’re going straight up with their engine, they’re all squished in their chair, straight up, and then part way along the engine runs out of fuel and shuts off, and then, just like throwing a stone in the air, it will go up and coast, and just get over 100k. And everybody will be floating weightless that whole time, as if they were a thrown champagne cork. They’ll go up and over the top and all float around weightless for a while, but then gravity wins. They’ll start falling again. …

Half the atmosphere is in the first 5 kilometres. … It’s almost like falling in a puddle of water when you fall from space, it’s not like a big sponge. … When they come down and hit the atmosphere, it will actually be six times the force of gravity as they come thundering into the atmosphere as a glider. If you weigh 100 kilograms you’re going to weigh 600 kilograms when you hit the atmosphere. So everyone is going to be squished like crazy until they can get slow enough that they can fly again. And then it doesn’t have motors anymore. It’ll glide down to landing with everybody sitting inside.

They’re charging about $250,000 a passenger. … It’s a big paper route, for sure. … Those people will be able to float weightless, and while they’re floating, he’s got windows all over his spaceship, they’ll be able to look outside and take pictures. Hopefully he’ll get it going within about a year. And I’m all for it. The government has designed a lot of the equipment, figured out the physics of the atmosphere. We’ve done a lot of the research that makes it possible. Maybe we’re just at the stage where it’s sort of like going from early airplanes to commercial airplanes, where you go for a profit. I hope it works. But it’s still a year or two away before the first one goes.

Q: What’s it like to use the washroom in space?

Want to come down and demonstrate? You were brave enough to ask the question. … [Motions speaker, Steve, to a chair.] There’s your toilet. …

It’s kind of a silly topic, but it’s important, all of us go to the bathroom every day and it’s a natural function. We’re evolved to go to be able to go to the bathroom using gravity. … So Steve’s on the toilet, number one and number two, and anything that comes out of his body he is counting on gravity to pull down into the toilet. Then once it’s in the toilet he doesn’t care what happens. He goes flush and it’s gone and the problem is solved. …

If Steve is going to the bathroom in space, the first thing that happens is he sits on the toilet and floats away. So we need to design a toilet that you wouldn’t float away on. It’s got a big seatbelt on it, so you sit down on the toilet and strap yourself in.

And then you think about the liquids and the solids. On a space ship, we want to collect all the liquids, recycle them, and turn them back into drinking water. Gross, but true. So you don’t want your liquids and your solids mixed. So there’s a special hose that comes out of the wall, it’s got a funnel on the end, and it’s got air pulled into it. When Steve pees into this tube, it goes through into a sewage collection tank … through big purification filters … and out the other end comes drinking water. …

Solids are a little different. They’re harder to recycle properly, especially in a small place, and it takes lot of equipment. We’ve decided to this point that we won’t recycle the solids. So the solids that come out of Steve’s body go down into a Russian designed toilet that’s got a little bag you put in each time. It’s air pulled down into the toilet that pulls stuff away from Steve’s body. … Then when you’re done you undo your seatbelt, you float up, turn around, just pull a little string. … It goes down into container that looks like a milk can, and then you put a new fresh bag in for the next person so it’s ready for them if they’re in a hurry.

Then when the milk can fills up … we store those on board. Our unmanned resupply ships, when they’re all unloaded, we fill them up with garbage, including our solid waste. When [one is] completely full… we undock it and it robotically flies away from the ship, falls down, and burns up in the atmosphere. So the next time you see a beautiful shooting star, that’s what it might be.

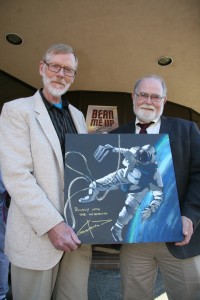

Inspired by Chris Hadfield’s mission, retired faculty member David Charbonneau (left) painted Floating in a Tin Can (acrylic, 2013). Hadfield signed it, “Boldly into the unknown”. Charbonneau donated the painting to the Faculty of Science—see it in the Bean Me Up Café.

Q: Do you have a tip for someone who would like to be an astronaut?

For an astronaut, number one is you have to have a proven ability to learn complicated things. … There’s a lot of stuff to learn to fly a space ship. What’s a proven ability to learn complicated things? An advanced university degree. If someone has a master’s in physics, or a PhD in bioengineering, this person has shown their ability to use their brain to learn complicated things. So that’s one. An advanced, complex education.

The second is, we hire healthy people. We don’t want to hire people who are going to get sick in space, we don’t want someone who is too fat to fit in a space suit. … We want people that are healthy. Part of that is luck… If you’re born with something that disqualifies you, so be it, get over it, get one with something that your body will let you do. … Accept the physicality of it, but at the same time, whether you eat your 15 pounds of ice cream or not, you can at least keep your body healthy.

So, advanced education, build yourself a healthy body, and the third part is a proven ability to make good decisions, when the consequences matter. We call that operational decision-making.

How do you prove to the selection committee that you can make good decisions when the consequences matter? We try and choose people like doctors who work in emergency rooms, because obviously they’ve made decisions under pressure. Or test pilots, people who’ve taken an airplane and put it out of control, and figured out ways to get it back under control before they crashed and died. Or someone who’s run a big program, if you’ve been responsible for a lot of people and money and lives, and proven ability.

It’s those three main things, career choice, advanced education, and physical health. That whittles it down to about 500 people. And then they’re looking for what else can you do? We don’t just want some super-fit student who made a good choice. We want someone who’s rode across the Atlantic, or who’s memorized Robert Service poems. An interesting person to fly into space with. It’s everything else you can do that will get you finally selected. But I would focus on those three.

And I wouldn’t just focus on those three to be an astronaut. Those are useful skills no matter what you want to do in life.

Q: What kind of personality traits make a good leader?

It depends on the purpose of the leader at the time. If the building’s on fire, you want one kind of leader. … If you’re trying to raise your children, or teach people values, that’s a different type of leader. Personality traits I think are very specific to the task you’re trying to lead the people to do.

I was the leader of the group of people that was living on the space station. …At any given moment, the space station—if we got hit by a little meteorite—would have a leak. Or, if our cooling system failed, we could have an ammonia breakthrough and contaminate the atmosphere, where you’ve got to get on masks within a breath. Or we could have a fire, and because it’s a closed environment, fire will kill you right away. So at any given moment I had to be ready to be that leader… absolutely dictatorial… there’s no discussion going on, we are all going to do these things right now to stay alive… we know I’m making the decisions and you’re going to do what I say. … You need that type of leadership sometimes.

But I was on the space station with five incredibly competent people. For normal times all I had to do was watch what they were doing… and make sure we knew what we were all doing, and that we were all sort of headed the same direction with our plan, and let people buy into it.

I also had a little bit of a nurturing and thinking process: as soon as I heard the earliest glimmerings that I might be the commander of this crew, I started working with those people, I deliberately sought them out. When you’re in a leadership position I would recommend this as well. As soon as you are given the task of leading another human being to do something, or a group of people, do your best to build a basis of experience with them, as early and as deep and as broad as you can. …

It’s sort of like a pyramid. If things go badly, it all comes to a point all of a sudden, and you don’t have time to discuss everything. You have to do things right as a group, so the broader you can make the base of your pyramid, the better your chances of succeeding when problems go badly. And that’s why the shared experience.

And sometimes you’ve got 10 minutes to do it. Like if you and I were in an elevator, and the elevator failed—or a group of any random citizens—you might have few minutes to talk with the other people around you… see who has a certain skill base, look at people’s personalities, recognize everybody’s strengths, weaknesses… and then make a plan and go forwards. Or you can all just scream and panic and do whatever you like. But if a leader is in that group, they will try and do those things. …

Get a common agreed-to goal, and then establish roles within the group that will get you to that goal. And get people to buy into the common goal as your fundamental precept of leadership. …

Q: How has your body changed being in space for that long?

[Hadfield asks the speaker, Arisson, to come up front as a model] Arisson’s body is beautifully designed to live on Earth, naturally. … It’s kind of an interesting design. …Our eyes are as high as possible, so we can see bad stuff, we can see saber-tooth tigers coming at us in the distance. So our eyes are way up here. Eyes are really complicated, so the big thick optic nerve that connects the eyes to the brain can’t be really long … so he’s got his brain up here, too. The brain uses a lot of blood, so therefore Arisson has a really complicated system in his body that fights gravity to squeeze the blood all the way up to his head, constantly, so that he doesn’t faint. … The heart is protected inside the big massive cage—because it doesn’t need to see danger in the distance—just like all the organs. And his body is working really hard to get the blood up to his head.

There’s Arisson, tens of thousands, millions of years on Earth, beautifully evolved and now suddenly—[lifts Arisson off the ground and upside down]—he’s weightless, floating around. So now most of those things don’t apply. His head doesn’t need to be on top, there is no on top, there’s no up or down…. His body has to make almost no effort at all to move the blood from his feet to his head. … He’s got this beautifully regulated balance system that uses gravity to tell him where he is…. You take away gravity and that’s completely wrong, useless information from his balance system. So, all these systems stop working. And, in order to hold this heavy head up, he’s got this spine, and this big heavy skeleton that when you take away gravity, he doesn’t need that, he could just be a jellyfish, to point his head around.

The first time Arisson pees in space, into that nice collection tube, his pee is actually full of his skeleton. Because by the first time you pee in space, your body has already said, “forget the last million years, I’m now weightless, I don’t need that calcium and minerals, I don’t need to hold my head up any more, so I’m going to start getting rid of my skeleton,” and it starts to evolve you to space flight immediately. His heart will start to shrink, because it doesn’t have to work nearly as hard. After six months in space, his heart will be smaller like the Grinch. …

He’s going to start turning into a Spaceling immediately, and after five months in space, he’s well on his way to adapting to a creature that doesn’t need gravity—which is fine if he never comes back.

But, now he comes home, and it’s a disaster. All the blood goes down to his feet, and his body has forgotten how to pump it up to his head. … His balance system has completely forgotten what to do with gravity, so now he’s getting these horrible, dizzy, spinning, conflicting messages from his balance system. And he’s got a weak skeleton, which is really fragile when he comes home. So then he has to completely readapt when he comes back again, has to learn how to balance again, his body has to learn how to squeeze his blood again, his heart’s got to get big and strong, and he needs to grow his skeleton back.

We’ve learned this over the last fifty years and we fight almost all of those things. … We can maintain everything except the density of the bones in the hips and upper femur, and I lost about eight percent of that. … I’ve got advanced osteoporosis in the lower part of my body, but it’s growing back. My body is reversing osteoporosis as I’m standing here crooked, it’s going “oh, you need bone, ok, I’ll grow bone for you”…. About a year after you get back, your bones are back to normal and you’re completely adapted, and you’re back to being an Earthling again.

A recording of the President’s Lecture by Chris Hadfield is available from the TRU Library. His new book, An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, was released in November.