Re Skú7pecen re Stseptékwlls. The story of Porcupine.

Re Skú7pecen re Stseptékwlls tells a tale of two groups who had different ways of doing things and often interfered with one another’s business. They had been enemies for a long time. Skú7pecen — porcupine — was sent from his group to travel far beyond the mountains, through deep snows to invite the other group to a feast. Once together, the two groups had to humble themselves before each other. To share wisdom, knowledge and learn from one another, creating a respectful relationship. From then on, they stopped fighting and prospered together on the land.*

*“This stseptékwll (story) was told to James Teit by Secwépemc storyteller Sexwélecken in 1900, only rendered in English as re-told by Teit in his own prose. The Skeetchestn Elders re-translated the story into Secwepemctsín. Kukwstsétsemc to Daniel Calhoun, Leona Calhoun, Amy Slater, Christine Simon, Garlene Dodson, Doris Gage, Marianne Ignace, Ron Ignace, Julienne Ignace.” – (paraphrased and published with permission from Qwelmínte Secwépemc) The Skú7pecen Telling. Accessed May 18, 2023, from the website www.qwelminte.ca/stseptkwlls.

The Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition (PLAR) team at Thompson Rivers University (TRU) followed a similar story. Like Skú7pecen, PLAR has journeyed long and often difficult academic terrain to work toward decolonization and to learn how to recognize Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing.

In July 2019, PLAR Director Susan Forseille invited 12 people who worked with Indigenous students at TRU to meet over lunch. As they ate, Forseille asked: Is TRU ready to decolonize PLAR?

“At the time, I didn’t know if that meant a separate PLAR process for Indigenous students or if we presented it all together,” Forseille says.

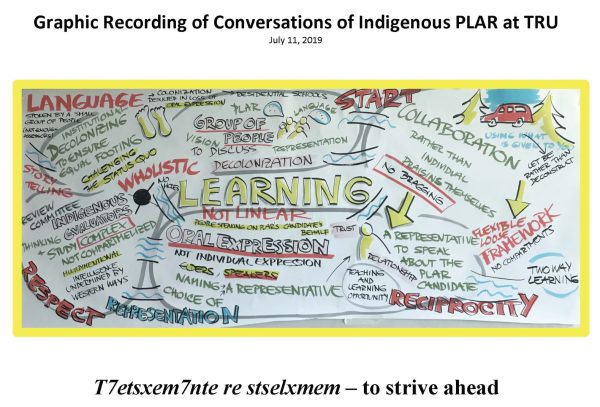

The insights into Indigenous learning that arose from this meeting — words and ideas illustrated into a graphic recording by artist Marie Bartlett — were eye-opening and supported the need to decolonize and indigenize the PLAR process.

“We came to realize that the colonized process of PLAR, with the heavy written piece, the compartmentalizing of learning and how it is evidenced, was not working,” Forseille says. “We wanted to develop a framework on how to shift PLAR from a colonial construct to something much less colonial and more Indigenous.”

Graphic recording of conversations about Indigenous PLAR by artist Marie Bartlett.

This meeting followed up on the results of previous research conducted by Forseille including the Persistence in PLAR, how to decrease attrition rates in post-secondary settings project conducted in 2018 and the What Can we Learn Through Indigenous Students’ Experiences with PLAR study conducted in 2019. In that study, Forseille reached out to students who self-identified as Indigenous and had gone through the competency-based PLAR process. She asked them if they felt safe, comfortable and confident articulating their Indigenous ways of knowing throughout the PLAR process. Of the six who responded, five said yes.

“However, when I dug a little deeper and looked at their portfolios, four of those six presented very traditional (westernized) portfolios.”

It was clear, that Indigenous knowledges were not being presented by Indigenous students because the PLAR process did not make it easy to do so.

Luckily, PLAR had a student who was eager to share his Indigenous ways of knowing.

Justin Young Thunder Sky

Justin Young Thunder Sky had been working through competency-based PLAR for a number of years and was struggling to complete the process to gain his credits.

“He (Justin) would start doing the work and then disappear for a bit and then come back,” Forseille explains. “We finally asked, ‘Justin, what’s not working for you?’”

Thunder Sky struggled most with getting his thoughts from his head onto paper, a requirement of traditional PLAR. Students have to write four to five pages for each of the eight required competencies — representing TRU’s institutional learning outcomes — to explain how their informal learning meets each requirement.

“Justin has tremendous learning and he has this amazing story, but our PLAR process just wasn’t allowing him to articulate it,” Forseille says.

Tina Matthew, TRU Executive Director of Indigenous Education, echoes Forseille’s description of Thunder Sky and his inspiring story of leadership and mentorship. She is excited Thunder Sky worked toward a way that TRU could recognize all his vast life experience as part of his educational journey.

Justin Young Thunder Sky presents Indigenous stories during an evening of storytelling at TRU’s Grand Hall in March 2019 as part of Indigenous Awareness Week.

Thunder Sky is a traditional oral storyteller and mentor who has worked as an Indigenous urban youth worker, youth facilitator and youth program developer/co-ordinator. He has travelled to more than 100 Indigenous communities to talk about healing, host healing circles and facilitate experiential learning processes to connect with one’s inner self.

He was, however, once a different man. He grew up in the midst of generational trauma and lost his parents when he was young, which lead to an unstable childhood in foster homes and ultimately, a life of addiction. Then, he chose to change.

On May 3, 2010, Thunder Sky embarked on a walk of healing from Kamloops to his origins in Bloodvein, Man. He walked 2,400 km over seven and a half months and with every step, he faced his past with forgiveness and love.

Since his walk of healing, Thunder Sky began working towards his degree at TRU while also supporting the campus Indigenous community as a peer mentor and transitions day co-ordinator. He was also key in decolonizing PLAR.

Finding new ways to recognize knowledge

“We worked extensively with Justin over a couple of years to really dissect what we were doing with PLAR, to see what was working and what wasn’t,” Forseille says. “We worked to determine how we could do things differently in a way that would recognize his knowledge while honoring his comfort and confidence in sharing what he’s learned and how he’s learned it.”

“With Justin’s help, we created a pilot project that allowed us the space and time to learn, do things differently and find a path to express Justin’s learning in a way that was rigorous enough for us to assess so the awarded credits wouldn’t be called into question. We were bridging Justin’s prior learning with TRU’s responsibilities and I am quite proud of all the work we put in.”

Matthew supports Forseille’s efforts and the strong Indigenous community involvement she accessed to ensure the Indigenous perspective was reflected in the project.

“Susan is such a huge asset to the Indigenizing of PLAR,” Matthew says. “She has always been open to talking to Indigenous faculty and has asked me for recommendations on Indigenous people that she could talk to. I’ve recommended a lot of faculty, Elders and community members and she’s taken up every resource that I’ve recommended.”

The work was exhaustive, with Thunder Sky, Forseille and the PLAR team investing well over a hundred hours into his portfolio and engaging in open pedagogy to find a way for him to express his Indigenous knowledge and learning in a way that was rigorous enough to assess.

Trial and error

“With every step we took, we thought how will this work, what else do we need to consider, who else do we need to consult with, what other people are going to help guide us,” Forseille says. “It was an extremely slow process.”

While the average student has 24 weeks to complete their competency-based portfolio, Thunder Sky had years to complete his out of necessity for the pilot project.

“In hindsight, I don’t know how we could have done it any faster,” she explains. “We had to give careful thought and have lots of conversations about what we were doing and then we would implement it and after we would have to analyze the results. We often ended up going through a lot of trial and error.”

As a traditional storyteller, Thunder Sky clearly presented his portfolio orally in a way he could not on paper. With Vernie Clement from the Office of Indigenous Education as his audience, Thunder Sky told the story of his learning and his Indigenous ways of knowing that translated into some of the competencies required for PLAR credit. This — in addition to two other videos highlighting Thunder Sky’s learning journey — was recorded, mapped out and time stamped with reference to where each competency was evidenced and then reviewed by PLAR assessors.

While some required competencies were present through Thunder Sky’s storytelling, others were not. And so again, through trial and error and other decolonized methods, the PLAR team uncovered more ways to support Thunder Sky’s learning and recognize key competencies.

For example, some of the students Thunder Sky was working with were interviewed and asked to describe the impact he had on them. Those interviews were touchingly powerful and shared the genuine voices of the 14- and 15-year-olds Thunder Sky mentored. They were also an integral part of his portfolio, which took a great deal of time to plan, organize and facilitate.

The PLAR team put a tremendous amount of time into planning a new, indigenized approach to interviews.

The interview

An interview is the final part of the PLAR process and is conducted over the phone.

Usually, in the final interview, the student works with two assessors who ask questions about the prior learning presented in their portfolio. The assessors then reflect on the student’s responses and the portfolio, and write a report with recommended credits. As PLAR director, Forseille reviews the report and portfolio, and determines what final credits should awarded.

“That’s what we do with most students, but Justin wasn’t a typical student,” Forseille says. “The interview is a very colonized thing that we do and we’d really given it a lot of thought on how to do it differently for Justin. He was engaged in the process all along and was helping us design what path he was going to walk.”

Ultimately, Indigenizing the interview for Thunder Sky meant using three assessors — two of them Indigenous — so there was better understanding of his Indigenous knowledge.

“Justin and I also talked about a smudging ceremony and a prayer to start things off in a good way,” Forseille says. “We also decided to video the interview.”

Despite all the forethought, consultations and open pedagogy, the interview did not go as planned.

“The interview started with tension and misunderstandings because I hadn’t given enough thought to how very colonized this process is,” she says. “This was one of our biggest mistakes but it also provided excellent learning for me as I realized just how careful we have to be, how much time and thought we have to give this process, how we have to talk to more people and how easy it can be to miss something so vital.”

Historically, Matthew explains that some Indigenous students leave education when there isn’t a connection or Indigenous-specific supports and understanding. She also says that many Indigenous students can feel their learning isn’t recognized because the colonized way of assessing learning, such as a pass or fail test, does not allow them to show what they really know.

“They (Indigenous students) don’t feel they belong,” she says. “For any student to fail on exams or tests time after time because they have different ways of understanding the knowledge they have been learning, well that’s a huge deterrent. That’s why we lose a lot of students, because of the ways we are assessing them.”

Ultimately, by decolonizing, Indigenizing and taking the time required to innovate a new and different approach to the PLAR process, Thunder Sky was awarded all the credits available to him.

Moving forward with a good heart

With the pilot project complete, Forseille worked with her team to analyze the outcomes. Those discussions focused on what it meant for students, what lessons were learned, what it mean for truth and reconciliation, and where it goes from here.

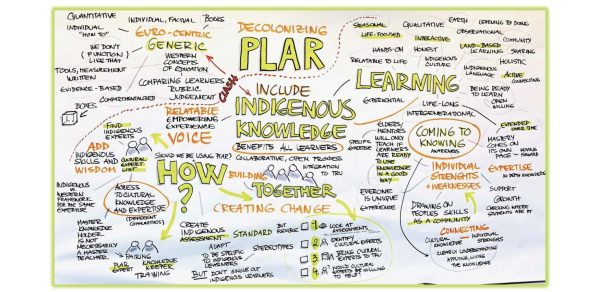

Graphic recording of conversations about decolonizing PLAR by artist Marie Bartlett.

The result? Three committees were formed; one focusing on interviews, another on the report structure and one related to the student handbook.

While many decolonization and Indigenization changes recommended for PLAR relate to the pilot project with Thunder Sky, some are also tied to the intensive research Forseille conducted.

“Our next steps are to visit the Bands and talk with them about PLAR,” Forseille says. “We’ve already had some of those initial conversations but we want to make it more formal and inclusive.”

Having strong Indigenous community members involved in the decolonization of PLAR is extremely important, according to Matthew.

“The Indigenous community really understand the student experience and the supports required,” she says. “They can provide input on the process that will help students.”

Forseille also hopes to develop a framework focusing on how PLAR can be shifted from a colonial construct to something more Indigenous.

Blending, bridging and rebuilding

“We have requested ISP (Integrated Strategic Planning) funding so that we can continue with this research and also conduct two pilot projects with two Bands and plan to create a cohort of these students going through competency-based PLAR,” Forseille says.

“We have also received funding to develop a three-credit course for PLAR, which will probably launch in January 2024. Everything we have learned from the process of decolonizing PLAR has fed into this course. So students will be able to choose between completing this course or the self-directed path we already have available.”

Ultimately, she hopes the work toward decolonizing and Indigenizing PLAR will benefit all students.

“We are working toward a gentler, kinder interview and our reports are going to be restructured,” she says. “We are blending, bridging and rebuilding the PLAR process and may do something really open with the pedagogy going forward.”

“That may be working with Knowledge Keepers and Elders so they have input into how learning should be assessed.”

Tantamount to all of the research and pedagogy into Indigenizing PLAR is the surety that the team does its due diligence to ensure the credits are deserved.

“Every person has their learning and we help them deconstruct it, reflect on it and then build it back up in a portfolio or a way that can be assessed,” Forseille says. “PLAR is one of the most progressive, innovative ways of assessing learning period and TRU is definitely the leader in PLAR.”

With more and more people sharing their wisdom and guidance and joining the path to decolonize PLAR, TRU is ready to go bigger and become a leader in Indigenizing PLAR at a provincial, and perhaps even national level.